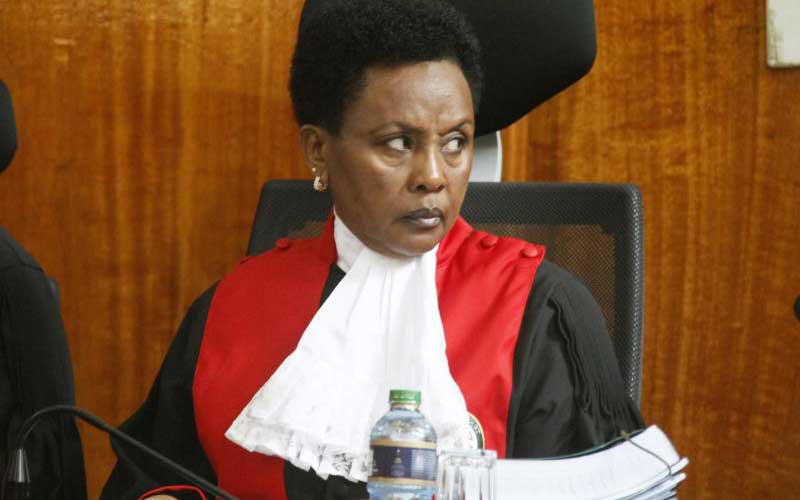

Acting Chief Justice Philomena Mwilu at a past court session in August 2018. [File, Standard]

In the first of our three-part series on the developments in the Judiciary, writer Kwamchetsi Makokha revisits Acting Chief Justice Philomena Mwilu's fight for survival when she was Justice David Maraga's deputy.

Justice Philomena Mbete Mwilu’s face was inscrutable on Monday as she stood at the podium in front of the Supreme Court building to bid farewell to the retiring Chief Justice David Maraga.

She appeared to have won the first round in a continuing bruising and bloody battle with the Executive that has lasted over two years.

Justice Mwilu stoically wears the tribulations she has borne over the past 877 days during which she has fought to retain her position as Deputy Chief Justice and Vice President of the Supreme Court, which allows her to act as the judiciary boss in the event of a vacancy in the office of the Chief Justice.

All pretense to government cordiality collapsed in the glaring absence of officials from the Executive and the Legislature at one of the Judiciary’s most significant events.

The Attorney General, who is also a member of the Judicial Service Commission and titular head of the Bar, and a former President of the Court of Appeal, was notably absent.

“The drums of war are beating already,” warned Chief Justice Maraga in his farewell speech to judges, “If you waver and do the wrong thing and this country descends into chaos, God will not forgive you.”

Justice Maraga leaves the Judiciary at a time when relations with the Executive are particularly sore, the President having failed to appoint 41 judges since they were nominated in July 2019, and senior officials openly disregarding court orders.

Last year, Justice Maraga advised the President to dissolve Parliament for failing to enact laws to include the right proportion of women in national elective leadership, attracting anger from the legislature.

Watching the Chief Justice publicly divested of his robes ceremonially while waiting to take over the leadership of the judiciary, albeit in an acting capacity, rang echoes of Justice’s Mwilu’s own abortive de-robing as a judge.

Expectations had been high that by sundown on August 28, 2018, Justice Mwilu would be wearing a zebra dress and orange sweater -- the ubiquitous inmates uniform that would usher her into Langa’ta Women’s Prison.

Detectives had earlier that morning dramatically seized the Deputy Chief Justice after a testy verbal exchange in the Chief Justice’s boardroom at the Supreme Court.

While she was being interrogated, the Director of Public Prosecutions addressed the media on the charges he would be bringing against her: abuse of office, obtaining security by false pretense, failure to pay tax and forgery on property transactions from five years earlier when she was a judge in the Court of Appeal.

At 4 pm, when courts were preparing to rise for the day, Judge Mwilu arrived in the magistrate’s court for her arraignment.

By a twist of fate, her lawyer who was to be charged alongside her, Stanley Mului Kiima, had already spent 24 hours in police custody and could not be held any longer without charge.

By that time, Justice Mwilu’s lawyers had also filed a petition challenging the charges against so that she did not take a plea and begin the downward spiral out of office.

Justice Mwilu’s petition questioned why she was being pursued for a bank loan and property sale transactions she had concluded more than five years earlier and claimed that she was being targeted as punishment for voting with the majority in the Supreme Court decision to annul the 2017 presidential election.

The Supreme Court’s annulment of the 2017 presidential election, only the fourth globally, sent shockwaves through Kenya’s political system and was celebrated as a blow for judicial independence but it provoked a relentless backlash against the institution and individual judges, including physical threats and budget cuts.

Justice Mwilu’s bodyguard and driver was shot and seriously injured ahead of major sitting of the Supreme Court in October 2017 ahead of the repeat election. The incident remains unresolved.

Nearly nine months after filing her petition, on May 31, 2019, a five-judge bench in the High Court stopped Judge Mwilu’s prosecution on grounds that charging her with abuse of office and forgery counts violated judicial independence, and that evidence in another five counts had been illegally obtained.

“Having found … that the DCI illegally obtained evidence against the Petitioner by gaining access to her accounts with [Imperial Bank Limited] through the use of a court order that had no bearing on her accounts and having found that the DCI thereby misrepresented facts and misused the court order,” said the five judges, “we have come to the conclusion that the prosecution against the Petitioner cannot proceed.”

Although the judges ruled unanimously, arriving at a consensus had left them with a bitter taste in the mouth at being forced to make the compromises demanded.

Within a week of that decision, Alexander Mugane lodged a petition seeking Justice Mwilu’s removal from office.

It would join an October 2018 petition by Mogire Mogaka and followed by another from Peter Kirika on June 11, 2019 and yet another by the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Director of Criminal Investigations petitioning the JSC for her removal.

On July 3, 2019, Judge Mwilu appealed some of the High Court’s findings, while the DPP and DCI challenged the entire decision eight days later.

With the two petitions lodged at the Court of Appeal, it appeared that the removal proceedings at the JSC would not proceed. Yet, twice in July 2019, the JSC informed Judge Mwilu – who represents the Supreme Court in the Commission – that four petitions seeking her removal were under consideration, and that she would be informed on next steps. She protested that these petitions reproduced allegations that had been decided on by the High Court and were in the Court of Appeal – to no avail.

Later, in December 2019, she objected to Attorney General Kihara Kariuki and Macharia Njeru sitting as commissioners in her JSC proceedings, and asked them to withdraw alleging bias, especially because the AG was a party in her cases in the High Court and the Court of Appeal. They both flatly refused.

The JSC was going at full speed ahead.

Acting Chief Justice Philomena Mwilu during her plea taking in August 2018. [File, Standard]

Such are the perils of the adaptations forced on institutions by the coronavirus that when the Judiciary elected to hold virtual sessions, Justice Mwilu entered an online JSC meeting in time to overhear a commissioner on the telephone discussing her matter: This, according to court papers.

“Yes, Mutongoria [Leader] …,” she heard a commissioner speaking to someone on the telephone.

“We must give it a date today. You know here we are in charge of our calendar. We must fix a hearing date. Not a mention date … a hearing date.

“In fact, the way this agenda is done, immediately after Panel 3 is where this matter will come.

“It is the only matter that is being heard by the full Commission and this matter must get a hearing date today. This matter cannot hold the bururi [country]. I have spoken to two judges. I had spoken to a judge, oh. At first, I had spoken to one judge.”

In court papers, Judge Mwilu claims that she confronted commissioner Macharia Njeru, the LSK representative, about this conversation and his retort was: “I will continue to be enthusiastic to clean up the mess in the Judiciary.”

When the JSC declined to compel the AG and Njeru to not hear the petitions against Judge Mwilu, and the two commissioners wrote separate explanations why they would not step aside from hearing the Mwilu matter, the Deputy CJ asked the High Court to stop the hearing of petitions against her.

The August 13, 2020 petition has laid bare the deep divisions

within the JSC, and the struggle to control the commission mandated with

defending judiciary’s independence, but more publicly renowned for

selecting the Chief Justice.

Chief Justice David Maraga hands over the Judiciary flag to acting CJ Philomena Mwilu (left) during his retirement ceremony at the Supreme Court yesterday. [Collins Kweyu, Standard]

Justice Maraga’s departure leaves a vacancy not only in the Chief Justice’s office but also in the JSC where he was chair. It is expected that Judge Mwilu will issue a notice of the Chief Justice’s vacancy, but applications will not start rolling in until mid-February.

Should Judge Mwilu apply for the Chief Justice’s job, JSC’s voting strength will be nine votes. With presidential appointees constituting four of the 11-member slots in the Commission, it is unlikely that the balance of power will remain in favour of non-presidential appointees.

In March, the term of the female representative of the Law Society of Kenya to the JSC ends and the position comes up for election.

Privately, Judge Mwilu – who enjoys a reputation for sharp tongue -- is reportedly stunned by the silence of her friends as she went through her tribulations but judges and judicial officers have interpreted her fight is their war.

“Without the rule of law, no one will be safe. Say no to impunity and maintain the rule of law,” Justice Maraga said in his farewell address.

As Judge Mwilu took the reins of the Judiciary, she is definitely aware of the transitory nature of her position: “For whatever period that it will please God for me to serve as the acting Chief Justice I shall ensure that we further entrench and build on your legacy and the judiciary shall forge ahead and continue its journey of transformation,” she said.

No comments :

Post a Comment