It did not seem like a revolution. A botanical green smoothie and a snapper fish burger, it was. In a Bahamas health food cafe.

But future generations might look back at this as a pivotal moment - the first national launch of a technology that could upend commercial banking and even shake the US dollar’s status as the world’s de facto currency.

The refreshments were among the first items bought using the Sand Dollar, a digital currency issued by the Bahamian central bank for use across the country via an app.

“It’s instant - I get a message, and it’s received,” said Dawn Sands, owner of NRG, the cafe in the capital Nassau, showing Reuters via video how sales work.

“Once people get comfortable and educated, I think it’s going to be big.”

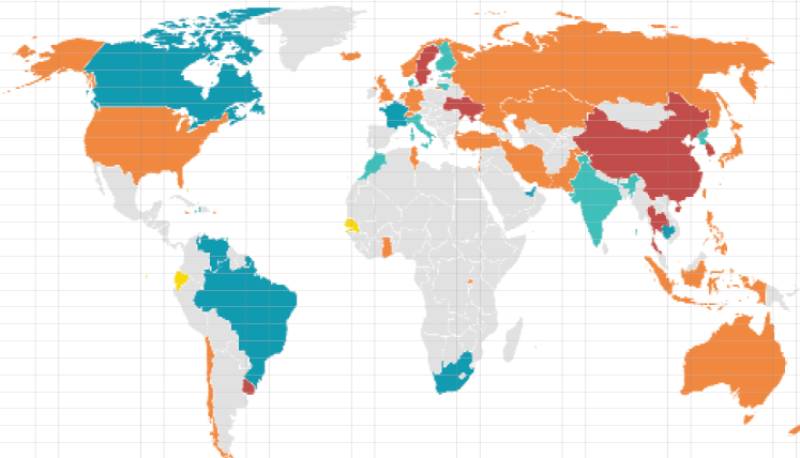

While this experiment in the archipelago nation of around 390,000 people is modest in itself, it is likely being closely watched by major central banks across the world, from the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank to the People’s Bank of China and Bank of England.

They have been looking at issuing their own digital coins, having found themselves in a tricky position as the use of physical cash dwindles.

Potential game-changer

They are wary of a blockchain-based technology like bitcoin conceived to banish central banks, but reluctant to miss the boat on a potential game-changer and cede the field to Big Tech offerings like the Facebook-backed Diem, formerly Libra.

Smaller nations such as Cambodia have also, meanwhile, forged ahead with their own projects in digital currencies, which promise to extend financial services to people currently lacking access to banking, especially in the developing world.

The Bahamian scheme offers clues for other economies on how central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) can be introduced and work in practice - from getting users on board to helping businesses avoid costly payments fees.

“Everybody is interested in it - I think it’s arguably the first step,” said Philip Middleton, deputy chairman of the Omfif central banking think-tank in London.

“If I’m looking for lessons learned for the big boys, it’s the whole education piece - if this is successful, how have you persuaded the population to use this?”

The Sand Dollar was launched in October, with users coming aboard in the subsequent weeks. One of its core aims is to boost access to financial services to people in the archipelago, whose complex geography of 700 islands and remote keys throws up challenges in securely distributing cash.

Payments are also a key area. At the NRG cafe, Sands said the technology would help smaller business avoid fees charged by credit card companies. She said she was charged around four per cent on credit and debit card sales of omelettes, panini and the like.

“For a small business, four per cent is a very big hit,” she said.

The virtual coin is issued by the Central Bank of The Bahamas to digital wallets held by an initial tranche of six licensed money-transfer and payment firms. Through them, people and businesses can then access, hold and spend coin via an app.

Three other companies, including a commercial bank, are undergoing checks for entry to the scheme, the central bank said, without giving further details.

The early signs are positive, though there are only $130,000 (Sh14.3 million) worth of Sand Dollars in circulation at present, central bank data shows, compared with $508 million (Sh55.8 billion) worth of traditional Bahamas dollars.

Interviews with the Central Bank of The Bahamas, Sand Dollar users and three of the financial firms offering the tech suggest that, so far, it is functioning as a way to pay.

“We have merchants right now that have come on board in terms of

integrating it into their system for persons to be able to purchase

products for them,” said Deirdre Andrews of Omni Financial Group, a

money transfer firm.

“The start of it is the movement of money back and forth.”

To introduce the virtual currency, the central bank launched a social media campaign on Instagram, where its workers discuss their experience of the pilot scheme.

“A key lesson is that stakeholder engagement is important,” said John Kim, general counsel for NZIA, the tech firm that developed the Sand Dollar.

“You can say, ‘adoption is important,’ but people need to use it - people need to get integrated into this.”

CBDCs are different from cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, though both are based on blockchain technology. They are issued by a central bank while bitcoin is produced by “miners” solving maths puzzles, with no central authority.

They are a complete replacement for notes and coins, also differing from electronic cash used to pay with cards or PayPal, which is merely a representation of physical money.

If there is a major shift from credit and debit cards to CBDCs, big payments firms and banks could see lucrative fees charged to process transactions evaporate.

In a sign of how some may seek to hedge the risk, Mastercard said in September it was creating a platform to help central banks test how digital currencies could be developed and used.

Bigger tests await with other larger CBDCs, with China the most advanced among major economies with it digital yuan - something it hopes could reduce its dependence on the global dollar payment system.

The Bahamian coin also does not allow individuals to hold accounts directly with the central bank - which could drain deposits from commercial lenders and shake their business models.

As such the project offers few clues to the impact of CBDCs on traditional financial firms, a key area of interest for major economies as they weigh the risks of the technology.

Kimwood Mott, who is overseeing the project at the central bank, said one attraction for many business owners had been the prospect of avoiding physical cash during the pandemic.

“It’s fast, seamless and - in the age of Covid - it’s safe.

No comments :

Post a Comment