Kenya’s capital Nairobi has just been disabled by record floods, forcing some roads to be closed.

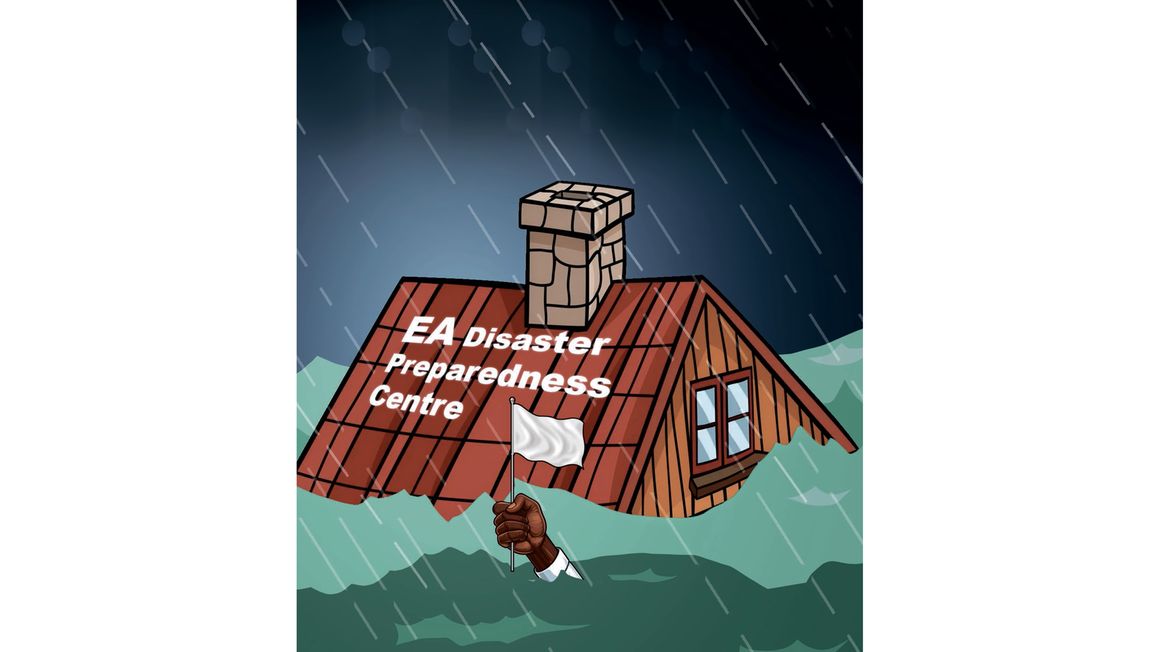

It is turning out to be the year from hell, in terms of climate disasters for

East Africa. As it closes the first quarter alone, nearly 200 people have so far been killed and thousands displaced by floods and mudslides as heavy rains pound the East African Community.Kenya’s capital Nairobi has just been disabled by record floods, forcing some roads to be closed. The property damage has been massive, with whole housing estates and business suburbs partially submerged.

In Uganda, the Kampala-Masaka highway, easily the busiest in the country, caved in — again. It was brought down by heavy rains last December. A critical Northern Corridor route, it is the main gateway to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi.

If last year’s pattern, in which the worst disasters, from Rwanda to Somalia, happened from May through to November, persists — with DRC witnessing its most destructive floods in 60 years —East Africa will be in a lot of climate pain by December.

Globally, even though natural disasters are getting bigger in scale, the deaths they are causing are reducing — everywhere, that is, except in Africa. Deaths from disasters are now becoming a governance and economic issue, with poor, corrupt, badly-governed countries suffering the most.

Take Taiwan. In 1999, it was wrecked by the massive Jiji earthquake, which killed more than 2,400 people, injured more than 11,000, and resulted in roughly $300 billion in damages. Early this April, it was struck by an earthquake of equal magnitude, the worst in 25 years. It barely made global headlines. Fewer than 20 people were killed, and just 1,000 were injured. The property damage was negligible.

Taiwan went all out on infrastructure resilience, with buildings, bridges and critical infrastructure built to withstand tectonic turbulence. They have stringent building codes and enforcement. And they built an elaborate national early warning system.

Some might say that it is an unfavourable comparison, given that Taiwan is a rich East Asian economy, whose gross domestic product of $791.61 billion is nearly twice the combined EAC GDP. So, there is Bangladesh, which would be very much at home if it were an African country.

Also read: Libya's reconstruction costs rise after floods

Bangladesh used to be brought to its knees and even beaten into a coma, by tropical cyclones and floods. In one of the most devastating natural disasters of the 20th century, in 1970, the Bhola cyclone claimed possibly up to 500,000 lives. However, Bangladesh got down to work and, over 40 years, it reduced cyclone-related deaths by more than 100-fold — from that record 500,000 deaths in 1970 to 4,234 in 2007.

Ten years later in 2017, when Cyclone Mora struck, there were only six deaths. Though these events have grown more severe, Bangladesh is close to ensuring zero deaths.

It created cyclone shelters and repurposed schools to double as cyclone shelters. It established a cyclone warning system with more than 76,000 volunteers, half of them women, who are trained in disaster management. Then the science kicks in; they arm them with the latest cyclone forecasts, and they travel through neighbourhoods, knocking on doors, and cajoling people through megaphones to take to cyclone shelters.

In the 1970s, Bangladesh had 100 shelters. Today, it has more than 5,000 which can shelter five million people.

Then it also did the building code and infrastructure remake.

East Africa can equal them because the most critical bits of their success didn’t need money. Or, at least, not a lot of it. In addition to the resilience measures and early warning system, both introduced a huge public awareness campaign, which includes educating citizens about what to do when floods and storms strike.

We can just copy Taiwan and Bangladesh and we will be fine. There are a few things that the EAC can do collectively. One of them is to build a robust EAC technology-smart early warning system. Artificial intelligence, in particular, has cracked this weather forecasting and crisis modelling in a big way.

Most of the things will probably have to be at the national level. Africans, in general, are hopeless swimmers, the result of which is that the region has drowning rates that the World Health Organisation not too long ago described as an “intolerable death toll.” The WHO lists Africa as the region with the highest rate of drowning deaths in the world, with about eight drownings for every 100,000 people, which contrasts with 1.5 people who drown for every 100,000 Americans, and Germany’s 0.6.

The situation is so bad that there have been reports of African “navy men” who can’t swim. One report said most of the police officers who patrol Lake Victoria — and are sent out to rescue capsized boats — can’t swim. Even many fisherfolks who make a living on the lake can’t swim to save themselves.

Read: Floods derail AU mission exit plan in Somalia

Millions of people have settled in wetlands and have to be relocated, and cities and towns built over rivers will have to be partially broken down.

Instead of national service in the army, governments should create ecological national services. Declare gap year for student cohorts and send them around the country in their millions to dredge lakes and rivers, and plant trees. Just two years of five million students a year saving Mother Earth would be a game-changer.

And, given the way things are going, in most of East Africa, except for the hilly bits, it should be mandated that houses must be built on stilts – or at least a metre from the ground. And all permanent homesteads should be required to have a small boat.

Charles Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer, and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. X@cobbo3

No comments:

Post a Comment