The president seems to be repeating the mistakes of Tanzania’s independence leader rather than learning from his legacy.

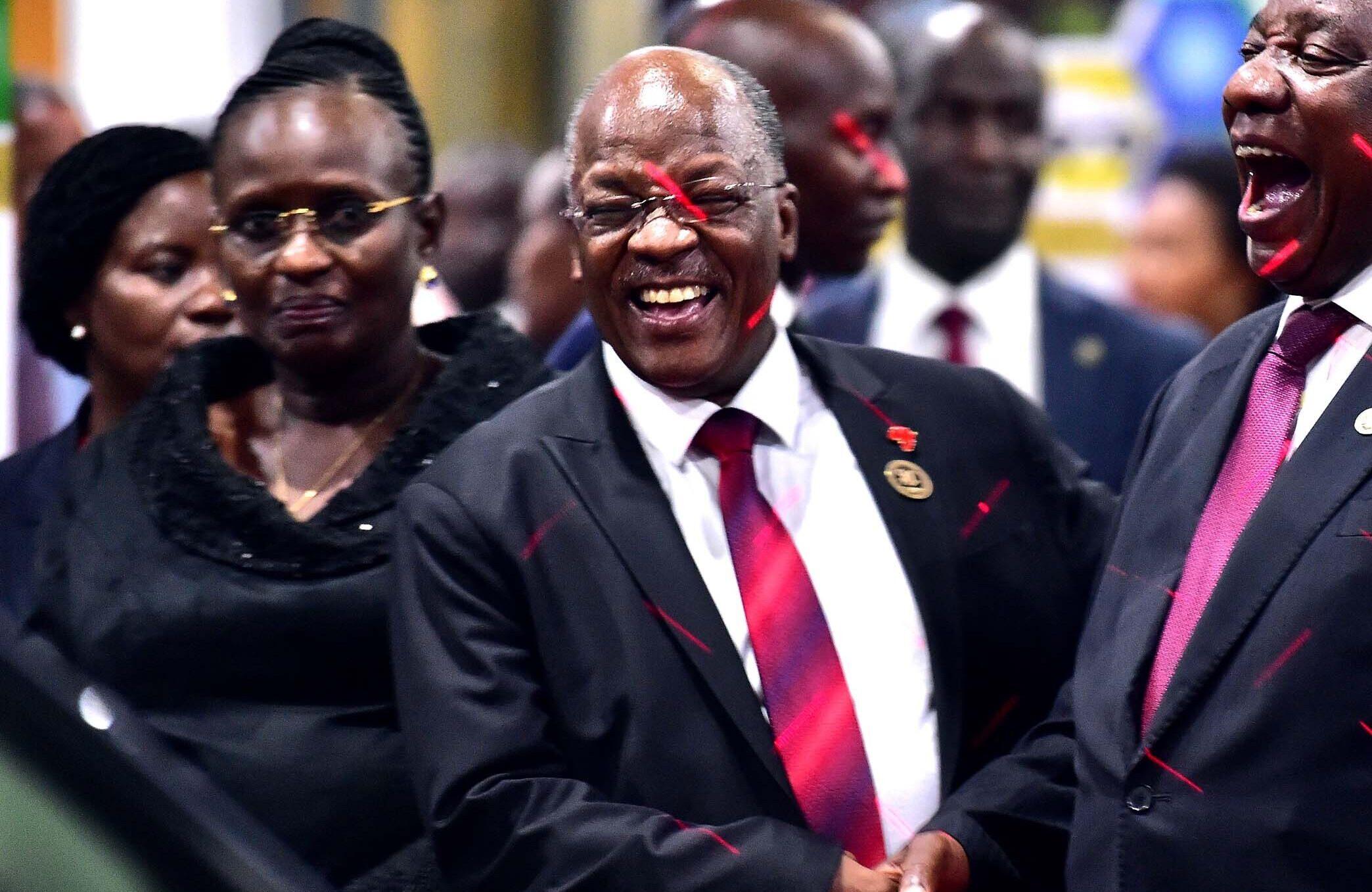

President John Magufuli of Tanzania. Credit: GCIS.

analysis By Nick Westcott

The president seems to be repeating the mistakes of Tanzania's independence leader rather than learning from his legacy.

I visited Tanzania

last month for the first time in five years and for the first time since

John Magufuli was elected president in 2015. I have been visiting the

country regularly since 1976, living there for a

year as a student in

1979 and for three years as a diplomat in 1993-6. I have followed its

fortunes through the decades with close interest, meeting all its

presidents (except the incumbent) at one time or another.

While I was there

on this occasion, the journalist and African Arguments contributor Erick

Kabendera was disappeared: that is, he was picked up by police and kept

incommunicado for several days until he suddenly re-appeared in court

and was improbably charged with economic crimes and tax evasion. This is

not a lone incident: since 2015 it has become common for independent

journalists to face harassment and even death, and for the government to

obstruct news or even the publication of standard national statistics

it dislikes. It is worrying both many Tanzanians and many of Tanzania's

friends overseas.

[I had to flee my home Tanzania for doing journalism. I was lucky.]

It is worth asking

where this new trend has come from. Since independence in 1961, Tanzania

has been a beacon of the liberation struggle in Africa and of peaceful

political stability. The country's moral and political compass was set

very firmly by its first president, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, whose

picture still hangs on many government, hotel and shop walls alongside

President Magufuli. All Nyerere's successors have appealed to and

pledged to uphold his legacy.

Nyerere's legacy

So what is that

legacy? Nyerere was relatively unusual among African presidents in that

he left a substantial body of writings that set out his political

thinking and which enable us to see its evolution. While sometimes

intolerant of criticism, he tended to respond with argument rather than

force. Nyerere's thinking changed over time, his ideas adapting in the

light of experience, but some elements remained unchanged: a powerful

moral tone; an intolerance of corruption; a central role for the state

but with a real accountability to the people; and, above all, the value

of unity at the national level, in the union with Zanzibar, and across

Africa as a whole.

Nyerere started as

an unabashed African socialist. Capitalism and colonialism had gone

hand-in-hand and destroyed many traditional communal values. These

needed to be restored and Nyerere justified Tanzania's one-party state

as necessary for building national unity and avoiding political

divisions. He also advocated ujamaa villagisation as a path to economic

and social modernisation.

Over time, though,

the president came to see the drawbacks of both policies. Although the

ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) had robust internal competition and

accountability, any single party that remains in power continually tends

to become complacent and corrupt. The target tends to become climbing

to the top of the party tree and reaping the benefits along the way

rather than serving the people. Meanwhile, villagisation and state

production proved socially disruptive and financially disastrous.

Economically, Nyerere's prescription just did not work.

In response,

Nyerere did two things. Firstly, he put in place succession arrangements

that allowed him to step back from running the government. Although he

retained oversight as CCM chairman, he stepped down as president in 1985

and allowed his successors to liberalise both politics and the economy.

In the 1990s, multi-party politics was re-introduced, a number of

loss-making parastatals that were draining the government's resources

were privatised, and the country began to encourage outside investors.

Nyerere's personal interventions became increasingly rare, limited

largely to upholding the sanctity and importance of the political union

with Zanzibar and working for peace in neighbouring Burundi.

Nyerere's legacy

was to value unity but recognise diversity, not overstay his welcome,

and be guided by principles but adapt his policies in the light of

experience.

Fulfilling or negating Nyerere's legacy?

Like his

predecessors, President Magufuli puts great emphasis on respecting

Nyerere's legacy. Selected at least in part for his well-known personal

probity, he entered office breathing fire and fury against corruption in

the state machine. His dramatic interventions appeared to shake state

utilities out of their torpor and corrupt practices. He developed and

delivered some basic infrastructure, including roads and energy. All of

this was overdue.

But in other

respects, Magufuli's administration seems stuck in the early Nyerere-ite

mode of suspicion, even hostility, to international capitalism and open

markets even within its region. It has returned to preaching a narrow

view of self-reliance similar to that which led the country to near

bankruptcy in the early-1980s. In political terms, Magufuli seems have

adopted an intolerance of criticism and opposition that Nyerere

abandoned in his later years. CCM seems increasingly frightened of

democracy, fearing that given a free choice and facts the people just

might choose someone else.

To constrain the

opposition and harass the free press will in the end destroy democracy

and even the CCM itself. We have seen elsewhere political leaders

deciding they should be the sole arbiter of decisions and stay on in

charge long after their sell-by-date, presiding over ever-more corrupt

and incompetent governments and leading their countries to wrack and

ruin. In almost all cases, it does not end well. The same can apply to

parties as to individual leaders.

Tanzania is a

country of huge potential. It is rich in land, material resources and

people. To make the best use of them for the benefit of its citizens, it

must also be rich in wisdom as well as morals. As everywhere, these

resources are best developed by a fruitful, harmonious and respectful

cooperation between insiders and outsiders. There is competition, but it

is best complemented by collaboration.

Tanzania has

benefited greatly from regular political succession in its leadership,

but it would be a betrayal, not a fulfilment, of Nyerere's legacy to

refuse the Tanzanian people a free and informed choice about the party

and policies they want. Mwalimu would probably be angry as well as sad

to think his successors had learnt the wrong lessons he was trying to

teach them - that they preferred a closed to an open society and were

looking to the past rather than the future.

This article was also published on the Royal African Society website.

No comments:

Post a Comment